Mastering DMAIC

Rome was not built in a day. Much the same when it comes to our ever-evolving mastery of running DMAIC projects. True mastery takes time, experience, effort, and investment in ourselves if indeed, we ever get there.

In a world where we’re faced with the everyday pressures of leaders wanting improvements completed yesterday, how can we develop our mastery – knowledge, skills, capabilities, and application – quickly? The lone voyage to DMAIC enlightenment might have its appeal but honestly, who has the time?

The route to mastery for practitioners is usually this. Complete your initial training, run some projects, and figure it out on the job. Train to the next level. Realize your mistakes. Repeat.

Essentially, it’s a learn-by-doing loop that takes many projects, considerable time, and investment.

It got me thinking. If our current level of DMAIC mastery is relative to our development, the work we perform, and our ambition, is it possible to achieve a higher level in a shorter time frame?

It’s a tricky question to answer. At some point in our professional or accidental careers as improvement practitioners, we’ve encountered the ‘oh’ moment. It feels a bit like looking up at the stars and realizing how small we are. Only, it’s related to our ability to complete the DMAIC project we’re working on. Some of those moments are technical things. Like when you realize you don’t understand regression, but you need to use it. Other moments are people related, where we’re just not equipped to handle them.

By writing this ‘DMAIC Projects – A Definitive Guide for Practitioners’, I hope that it moves you a few steps closer to your mastery of DMAIC.

Let’s get started.

An introduction to DMAIC

DMAIC is perhaps the most versatile method for undertaking business improvement. It originates from the 1980s and has seen a few changes over the years too, the most significant being the integration of Lean to form Lean Six Sigma. This extended the tools available to us when running projects under DMAIC.

Historically, we’ve been taught DMAIC by a linear walkthrough of the phases. Within each phase, we learn the plethora of tools available to us. Create our charter in Define, create a baseline in Measure, and so on. The technical difference between Green Belt and Black Belt is simple. More tools, some of them to a greater depth, and an expectation that Black Belts will lead bigger, more complex projects. Repeat for Master Black Belt only with a programme view.

When we’re in training, it all seems good. Yes, there’s a lot to take in but we all survive!

It’s not until we’ve completed a few projects that we start to learn and understand the harsh truth of leading DMAIC projects.

Truth #1

Our training didn’t go into enough depth on the things that involve working with people.

Truth #2

No one told us which tools we should use to solve the problem we’ve been given, nor how various tools can be linked together to increase success.

Truth #3

The practical realities of coming up against messy data can make it hard to extract meaningful results. The real world is so different from classroom exercises!

Truth #4

We weren’t prepared for the complexities of leading the project whilst managing the expectations of our business on solutions, timeframes, budget, and expectations.

Truth #5

In the pressure cooker of leading our first few projects, it’s been a struggle to get the project to complete.

In this guide, I’m not going to cover “how to perform tool x” in detail as that’s been done a thousand times. We will reference tools, but I’m going to assume that you have covered those in your training or that other articles on this site or Google can and will fill in any blanks.

Instead, I’m going to take a different approach. Yes, the guide will be structured as D-M-A-I-C but within each phase, and across phases, I’ll look to solve the truths listed above whilst keeping a firm eye on the business outcomes. In essence, this Definitive Guide to Running DMAIC Projects will take you through the process of leading a project; all the good bits, many of the ugly bits, and close a lot of gaps. At the end, I hope your mastery of DMAIC will have been raised.

Define – Getting Ready to Rumble

Let’s start with the purpose of define.

To me, there’s only one goal. Get the project underway on the soundest basis possible.

That goal has a dual focus on progression and path. When we launch a new project, our first thought should be; how do we get this project on the best path we can?

Projects can take many different paths depending on the choices that we make.

So how do we get ours on the best path?

Focus on these six questions.

- Are we working on the right problem?

- What benefits are we aiming for?

- Who do I need to work with to secure these benefits?

- What constraints are we working with?

- How do we break those constraints?

- How can I structure this project to complete quickly?

Notice the total lack of tools in those six statements. Tools exist to help us shape progress, but it’s the progress along a path that counts.

The Soundest Basis Possible

In the above goal statement, the words soundest basis are very deliberate. The intent is to convey that perfection is not required for progression.

When we run DMAIC projects we are always faced with uncertainties, constraints, risks, and unknowns. Usually, we cannot manage all of these away before we start, so instead we must embrace them. We recognise them for what they are and look to resolve them as we progress.

Soundest basis means that we understand what we can right now and are happy to proceed because we assess that the impact is manageable.

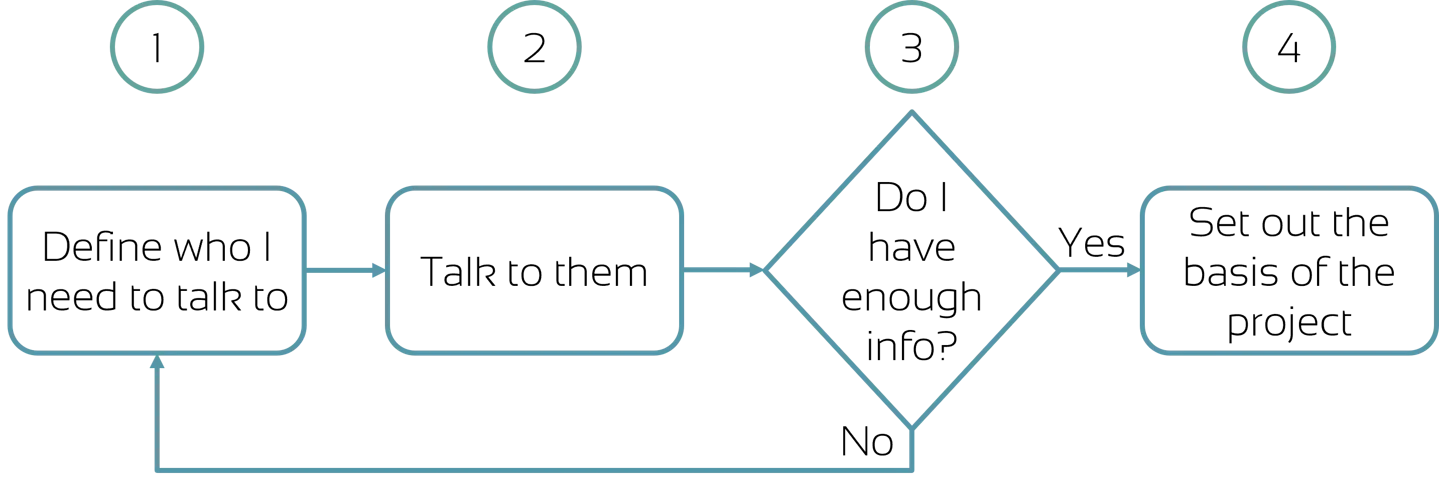

To answer the above six questions, use this simple four step approach.

That’s not the most difficult process to follow! However, underneath, it’s all about working with people. Often senior people over whom we have no organizational authority.

My first pass through steps 1 to 3 is always with just one person, my sponsor. To me, this discussion is very important, so much so, I’ve written an article on just this topic – Project Validation.

After talking to the sponsor, I may need to loop back and speak to other stakeholders, which I’ll schedule and do. Usually, these conversations are not as detailed as they are more focused on filling in gaps or confirming understanding. The one exception is the process owner whom I’ll quiz deeper.

Then I’ll then assess if I have enough information to start the project and if so, I’ll reach for my charter doc and complete that in step 4.

So, the critical part of Define occurs when we talk to our stakeholders in steps 1 to 3. In these conversations, we focus on getting clarity on these six questions. Let’s explore what that ‘clarity’ looks like.

1. Are we Working on the Right Problem

Answering this question is the most important part of any project. Getting it right takes effort and skill but failing to get it right will set your project off down the wrong path.

“Are we working on the right problem?” A simple question that is sometimes very difficult to answer. In my discussion with stakeholders, I look to firm up two things. Clarity on the problem and confirmation of the priority.

Clarity of the Problem

Attaining clarity of the problem centers on developing the problem statement and the scope until both are fully defined and acceptable.

Any problem statement must be clearly defined. It is a description of ‘what is wrong with what’. When our problem statement is clear, we can organize and motivate our project team and impacted groups around it.

A validated and concise scope that wraps around that problem statement is also important. If the problem statement is the thing we’re trying to solve, then our scope is our guardrails that constrain the problem. Projects can enter ‘boil the ocean’ territory when their scope is poorly defined. This is a never-ending space of continual project activity without outcome. It’s not a fun place to live, especially if significant benefits are attached.

Clarity of the Priority

Reaching clarity on the priority means we understand and have confirmed where this project sits relative to all others in the organization. The project priority itself is formed out of the size and importance of the issue, the benefit opportunity, and the strategic fit. The strategic fit could be defined from either the perspective of our total organization or our department. It depends on how structured and integrated our company’s improvement activities are with the overall strategic goals.

When we are happy enough (remember the ‘soundest basis’ principle), document it. This is the point we reach for our charter, which we’ll cover later.

2. What Benefits are we Aiming for?

Defining benefits upfront is one of those tricky aspects that you get better at over multiple projects. At this stage of the project, things are little more than an educated guess so it’s important that your stakeholders are helped to understand your benefits and how those benefits will be managed through the project.

There is only one rule about benefits. Aim high, very high.

How do we set benefits? Over many years, this has become my preferred approach.

Communicate to stakeholders how benefit management works

We do this by saying we will create an initial best guess which will then be refined through the Improve phase and confirmed in the control phase. It’s important that stakeholders know and accept that benefits may change. The primary reason they change is because, at this point, we have no idea what the solution will be.

Set the bar uncomfortably high

Usually, benefits are conditional on the amount of change we think you can make. Largely, this is an unknown at this stage so my advice here is to go large.

For example, if I was asked to streamline a process, I might be tempted to aim for a 5% reduction in lead time. But I know that in a process that’s never been leaned before, 5% can be achieved with my eyes shut and one hand tied behind my back. So, I go large here but not stupid. Based on my initial conversations I’ll maybe pitch at 30-60%. That should create acceptable benefits and should be enough to scare the team. If the team aren’t scared when you share this goal, then it hasn’t been set high enough.

Scaring the team a little bit with a stretch goal is healthy. Get them focused on reaching or exceeding it. But don’t petrify them with some 80-90% target reduction. We need them to act, not hide in the corner.

Create benefit estimates

We can then convert our goals to form initial benefit estimates. I recommend creating a range rather than a point estimate. Describe this range to stakeholders as “at this stage, we expect benefits could be as high as X and as low as Y”. The psychology of this is to create anchor points at both ends where people will remember the last number more than the first. If you just use a single point, that becomes the anchor and people being people will frame their expectations accordingly. Now, we should put in some work to define these, but we’ll save that for another article.

3. Who do I need to work with to secure these benefits?

We can’t avoid it any longer. It’s now that time when we must move into the murky world of stakeholder management. This is perhaps, the most oversimplified aspect taught in Lean Six Sigma.

The term ‘stakeholder management’ is one I’ve come to hate. We don’t manage stakeholders; we work with them. In practice, it’s a far more collaborative activity.

Identifying, prioritizing, and then defining how we will work with stakeholders really means ‘How can we work with these people to help our project deliver the benefits?’

As not all stakeholders are equal for any project, I have a process I use to define the identification and prioritization aspects which you can read about in this article – Key Stakeholder Priority, F1 Style.

Forming relationships and generating understanding

The actual working with them becomes very personal to you and your own style. Textbooks will say it is primarily about building relationships. Kinda. Yes, it is about relationships, but perhaps more importantly, it’s about understanding their perspectives. The perspectives our stakeholders hold dear will do more to impact our project than our relationship.

I’ve known many stakeholders that I wouldn’t choose to share a teaspoon with, let alone a cuppa (and no doubt vice versa!), yet we’ve worked together successfully to achieve good results. I find that once I can squeeze into their shoes, I can usually find ways for us to work together.

You can read about one such exploit in this article – Resistance To Change.

This doesn’t mean acquiescing to every demand. That’s a route to disaster. Moreso, it means taking their perspective and testing it for truth. Often stakeholders form perspectives on processes, teams, products, customers, and performance that are not 100% true. Sometimes all it takes is a little non-politically aligned data and facts to be presented to switch the view or to challenge it sufficiently, such that peer pressure does the rest.

When I work with stakeholders, I do so on two levels. An individual level where I’ll always talk openly about the project and their involvement, and collectively where I may need to challenge or guide the group. Honesty is critical. I remain staunchly independent and politically neutral – the Switzerland of the project – I never, ever take sides.

4. What constraints are we working with

Another area that is under-taught in LSS training is that of constraints. We’re often told to manage our risks and issues, usually as part of a light skim through project management but rarely are we taught about constraints.

Identifying constraints

In project management, a constraint is something that limits us in terms of time, cost, scope, quality, resources, and risks. Since DMAIC is a project, we can apply these to our activity as well.

A simple example would be that a team member’s time is restricted due to other priorities. That would be a resource constraint. Another example would be that we can’t access the production facility to run tests except on a Friday afternoon. That’s another resource constraint.

Many are simple and obvious but others are less so, especially to the new practitioner, such as:

- Your nicely defined scope is a constraint in that it limits us to our area of focus.

- We might have timelines imposed on us due to other project dependencies.

- We might have identified a risk that will hit on a specific date. That date, therefore, becomes a constraint.

Managing constraints

The key to constraints is that we need to recognize and manage them. In big formal projects where the solution is known up front and led by a Prince2-certified project manager, managing constraints is second nature. For your average part-time DMAIC project leader, belt certified or not, mention constraints and nine times out of ten a blank look comes back. It’s a different ball game.

Managing constraints isn’t particularly difficult to do. It does tend to be pushed to the back though, especially when you’re not an experienced PM and you have a hundred other things to do each day. Unfortunately, that introduces risk.

Risks occur when constraints are not managed. The classic example is that of a change to scope. Changes in scope whilst running a DMAIC project can create havoc.

Add another site location to the scope. Suddenly, you have additional stakeholders, perhaps different ideas on solutions, different change control teams, more complexities in the deployment and timings, let alone the additional off-site project team members to involve because of that travel ban.

Because of these knock-on effects, every change to a constraint needs to be assessed in the context of impact on the delivery of the project.

This brings us back to having the experience to a) do that assessment of impact well and b) have the confidence to go back to your sponsor to talk about the impact. Talking it through is critical since more often, it’s either our sponsor or a senior stakeholder who has broken the original constraint.

I’m a firm believer that projects should finish. You might find that a curious thing to say, but far too many don’t. The main reason they don’t is because somewhere, at some time, a constraint was loosened. It’s often scope, but not always.

5. How do we Break Those Constraints?

Constraints are also testable. Just because someone says we can only use Tony on a wet Thursday afternoon doesn’t cast that into stone. If our project has priority, then use it as a lever. Test that constraint. Ask why? Also, ask what can we do to free more of Tony’s time. How can we help? Who else might be able to help?

There are always options. A bit of cover for Tony, a temporary resource brought in. The answers are there but they always relate to priority and benefit.

Instead of the project taking 9 months due to Tony’s availability, think about how you can complete it in 3 months. This leads us nicely into our final element.

6. How Can I Structure This Project to Complete Quickly?

Use Workshops, Not Meetings

If you haven’t yet worked it out, most leaders like things done quickly. Especially so if their name is linked to the project. Double that if there’s a large pot of benefit waiting at the end.

Our mission is to design our project to complete in the shortest possible timeframe. And that means we need to think creatively about the best way to move this project along.

Workshops are our delivery vehicle for success. Whether that’s one, five, or more days at a time is up to us, but nothing moves a project faster than a workshop. They are great for focus, energy, morale, and commitment. We can use them to break our constraints as well. “If I can have Tony for 3 days that week, would it be easier to get cover?”.

What to avoid? Death by a thousand, one-hour, once-a-week, meetings. Honestly, no project can succeed this way. Progress is painful. In the meeting, we spend half our time remembering where we are in the project. Twenty minutes hearing excuses because people haven’t completed their actions (hint, they’re too busy). And ten minutes working on the project. These projects are high contenders for never completing or they take 9-12 months or more. That’s unacceptably slow.

If we can’t run workshops then minimum meeting times should be two hours and cover specific pre-defined, planned out, and communicated in advance, activities. Preferred meeting times are 3-4 hours. Make it long enough to keep things moving along.

Make DMAIC Rapid

If you want some guidance on how long a rapid DMAIC project should take, a good rough outline starter schedule is this.

Rapid DMAIC Outline

Total time: 4 weeks (rapid) to 12 weeks (good)

I usually start with this rapid delivery intent in mind. Depending on the type of project, which I’ll have a good feel for by the end of Define, I’ll then firm up an outline schedule. My aim is always to get to a solution design in the shortest possible time.

In some projects, typically reasonably well scoped lean-only activity, we can combine all the remaining phases into one workshop, effectively doing M-A-I-C in one hit. These are often referred to as Kaizen Workshops or Workouts. It is possible that the fully M-A-I-C activity can be completed in one to two weeks using this approach.

In other projects that need more work on the solution, both of those middle Improve phases can be extended. You won’t necessarily know this until you get into Improve, so this is always something to watch for and have a disclaimer in place with your sponsors that the timelines may adjust.

I’ll explain overall project completion times to stakeholders like this, “We won’t know the exact timeframe for completion until we know the solution, so while I can be confident in how long it will take to get to the point of designing a solution, the remaining timeframe may change. We’ll keep you updated through the project.” I’ve yet to encounter a stakeholder who says that’s unreasonable.

Define Summary

There are a few things to call out for Define.

- As practitioners, for the most part, it’s down to us. We won’t yet have a team formed so the work naturally falls on us.

- The degree of success is fully dependent on us and our stakeholders reaching a practical, pragmatic agreement on the project.

- Don’t overcomplicate it. When working through these six key questions, balance the depth, scale, and opportunity of the project.

Lastly, we should document the intent of the project, and typically that goes into the project charter.

I’m often asked, “How much detail do I put in the charter?”. My answer is always the same, “as much as you need to convey the project to your stakeholders.”

The depth of content in a charter will differ in every project as it is project dependent.

If our project is resolving a single quality issue on one process in one location, then our charter is likely to be quite small and light.

For larger cross-functional, business-critical, worldwide, process simplification activities, then it’s more likely we’ll need additional depth and detail.

Charter documents are often shared, so it needs to be readable and understandable by the audience.

I like to give the charter to the team and have them give me their individual interpretations of it back. If I don’t get too much variation, then it’s good to go. Otherwise, I know it needs work.

Measure – In God we Trust, all Others Bring Data

I’ve always found the Measure to be a phase that confuses many people. Predominantly, that appears to be because people are uncertain about what to measure as there are so many things that could be measured.

There’s also a blurring between Measure and Analyse. With today’s tools and digital storage of data, we can obtain, structure, and analyse data almost immediately so it is common that these phases blend together.

The purpose of Measure is to establish a high-quality baseline of current performance, such that we can assess today’s performance and evaluate our changes.

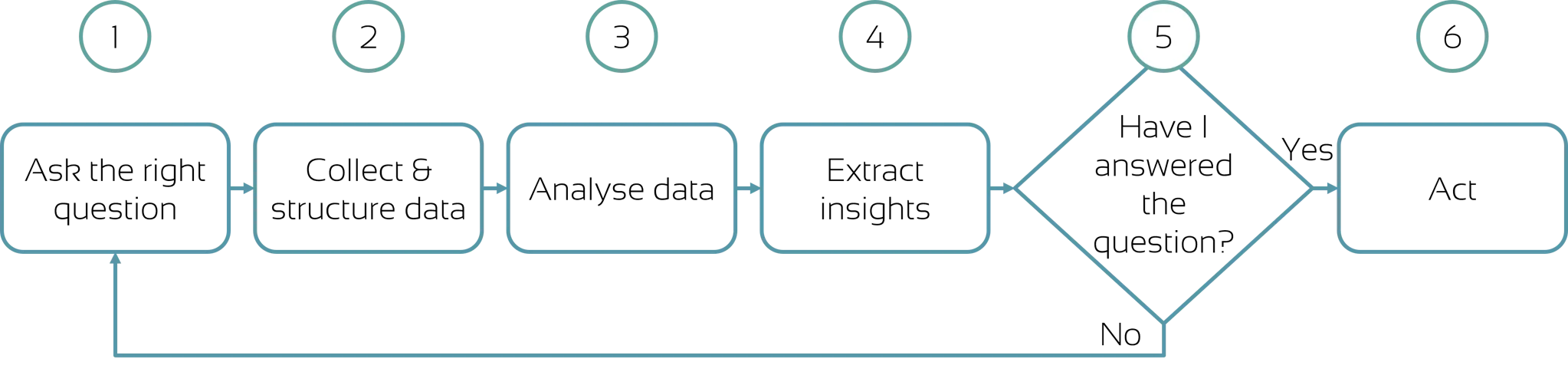

Questions. Really good questions.

The Measure phase doesn’t start with collecting data. It begins with a brain exercise to form the questions you must answer to solve the problem in front of you. Asking great questions is fundamental for generating higher-than-normal benefits. However, creating great questions is not straightforward.

One day I received a call from an ex-Black Belt student who trained five years previously.

“I finally understood it!” they said excitedly.

“OK…, understood what?” I asked.

“In our training, you said that asking the right question is very different from asking any question. That, great questions get straight to the heart of the problem and can transform the direction a project takes.”

“I was always troubled by that because I couldn’t see the difference until now. I just asked a question about our problem that was sharp and to the point. It was brilliant and showed us exactly what we needed to do to understand our problem. I was so excited I just had to call!”

Ordinary questions give up ordinary information.

A great question will give us actionable insight. Data scientists like to use the phrase actionable insights. While that term has been kicking around for decades, it’s nice to see it finally getting mainstream attention. It is precisely what we are aiming for.

What is it that differentiates an ordinary question from an actionable insights question?

Data and Information Questions

Let’s say we’re looking at a problem where our widget production line sometimes meets our daily customer demand of 3000 widgets a day and sometimes doesn’t.

An ‘ordinary’ question might include:

- “How many of these widgets did we process this week?” Answer, 14,700.

- “What was our daily production?” Answer, 3050, 2950, 2850, 2900, 2950.

What have we got back from our questions? Plain old data. Honestly, so what? Who cares?

We can extend that ‘ordinary’ question into another marginally less ‘ordinary’ question. Such as:

“What was our average daily widget production last week?” Answer, 2940.

This gives us information. We see it all the time in tables of data. The data might be summary statistics, like averages or counts. It is still just information. People pour over these tables in businesses looking for patterns and trends. Bosses ask, “Why were we below average yesterday?” and “Who is doing something about it.”

As before. So what? Who cares? How does guessing help solve our issue?

Actionable Insight Questions

Then, as the DMAIC project lead, we turn up and say: “Ahh, OK. Why don’t we put that data on a control chart and explore the process stability and the variation? We’ll discover if we have a process centering issue, a process variation issue, or both. If the process is stable, we should look at capability too. Compare the process to the customer’s need. If we’re running predominantly under customer demand, we should assess takt time and explore which wastes we can remove.”

That’s a set of questions to give us actionable insights. We might not get a final answer, but these questions will lead us the right way.

With questions that illicit information, we are guessing at the right path. Questions that give rise to actionable insights guide us along the right path.

When we have defined our set of questions for our project, we can then collect the data to answer them.

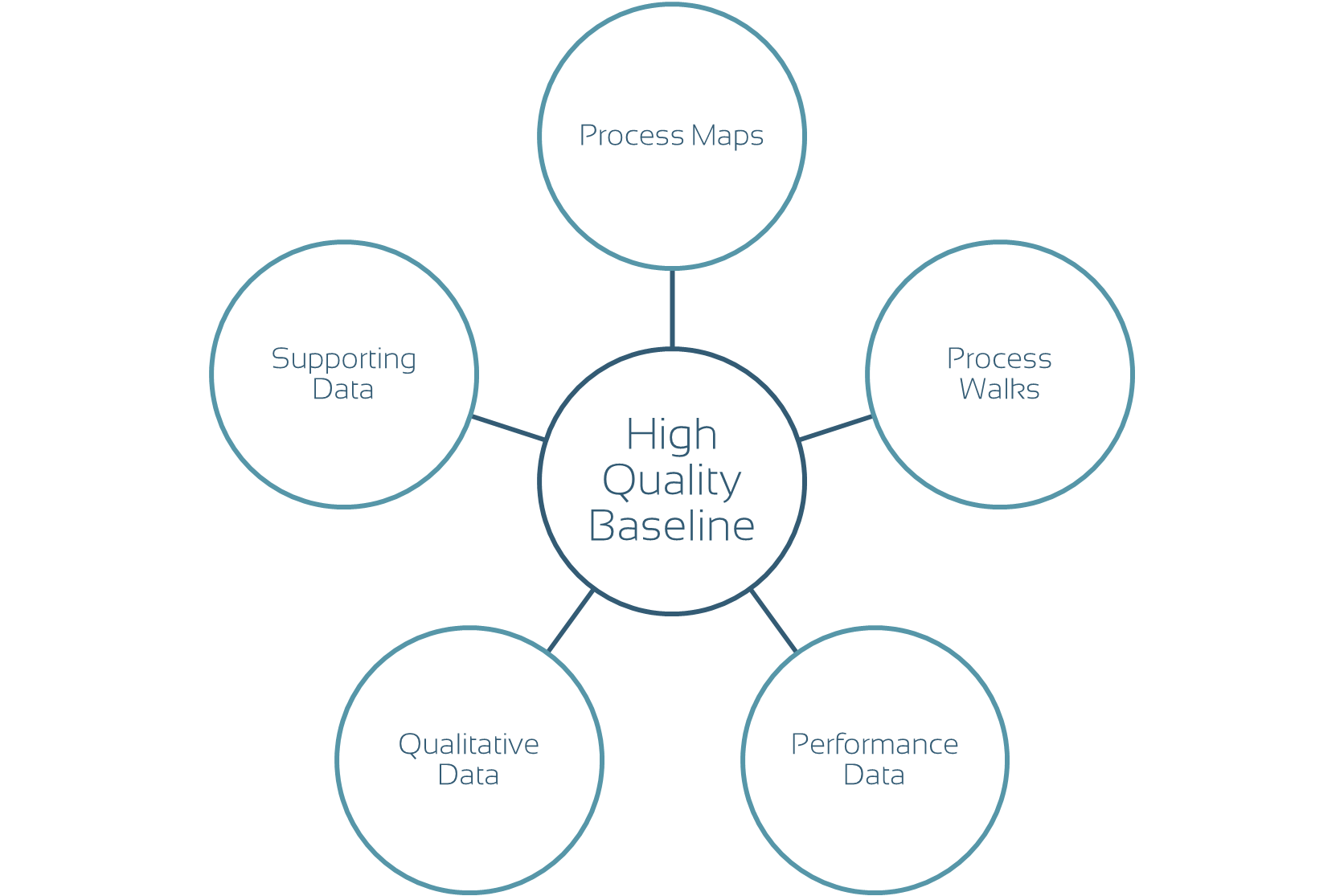

Creating A High-Quality Baseline

So, what makes a high-quality baseline?

There are five main elements that, when taken together, give us the ability to understand current performance.

Obtaining that data is the Measure phase. Understanding it is the Analyse phase. Actioning it is Improve.

1. Process maps

Swimlane maps, spaghetti diagrams, flowcharts. Use these to get an overview picture of the process. Overlay data obtained from other sources on the maps to bring them to life.

I love process mapping sessions. They are the very first thing I do when I bring a new group together, either within a workshop or as a half-day event. It is fascinating just how much insight you can get from a project team in a mapping session. I lead them to be inclusive, high energy, fast-paced and outcome orientated.

Cover the walls. Let people see the complexity of how they work.

Our aim isn’t for perfection or too much detail. It is to obtain a representative and agreed view of the activities, decisions, flow, and ownership of the end-to-end process.

When we’ve got that, we move on to element two below.

2. Process (Gemba) Walks

Straight after we complete the process map it is time to go and see the process first-hand. It’s here that we capture the detail within an activity. It doesn’t matter if we go and watch a production line or sit next to someone keying in data, as there is always something to learn.

A step on a process map might describe an activity as Process Expense Receipt. Observing the person who actually process those Expense Receipts reveals the detail inside, including the wastes. If we send team members to observe different parts of the process, make sure they take copious notes, or preferably video. Bringing the detail back into the project room and sharing is excellent for understanding.

Walking the process helps with change management, too. Involving those working in the process by expressing interest in what they do helps develop support for our project. Ask them lots of questions, especially on things that go wrong, cause frustration, and waste their time.

3. Process performance data that is related to our goals

How much data?

Too many projects either collect historic data over a too long a period, or too few items. And they do it across too many metrics.

- Collecting too much data results in losing weeks or months analysing it. Finding genuine insights during the Analyse phase becomes more difficult.

- Conversely, too little data will lead us to conclusions that may not represent the true process. In essence, we risk making decisions that are based on random chance.

If data enables us to understand performance related to achieving our goals, or answering our questions, then collect it. Our data collection plan exists to help us clarify this purpose. It makes us think about the data we want, and how we will get it.

Historic data

Using long term historic data may contain unknown process contexts. A process context is simply a state of operation. As many businesses do not keep detailed records of every change made in a process, their historic data contains all the changes made in that period. We will be non-the-wiser and will treat it as all the same system. That’s always a bold assumption, made knowingly or not.

The only benefit of historic data is to see trends or step changes. We still need to try and understand them. Are they caused by something that we don’t yet know about, or are they just process drifts that occurs naturally over time? The latter is often seen with periods of stability that move up and down.

Sampling

No, sampling is the way to go. At this stage, take sampling to read: define a sample size and collect an unbiased, representative dataset. Setting a sample size requires knowledge of hypothesis tests, which I recommend every project thinks about for every goal metric. After all, if you want practical proof of a change, statistical proof is sometimes a necessary precursor step.

By sampling the process, we are obtaining a reliable amount of data to describe that performance characteristic.

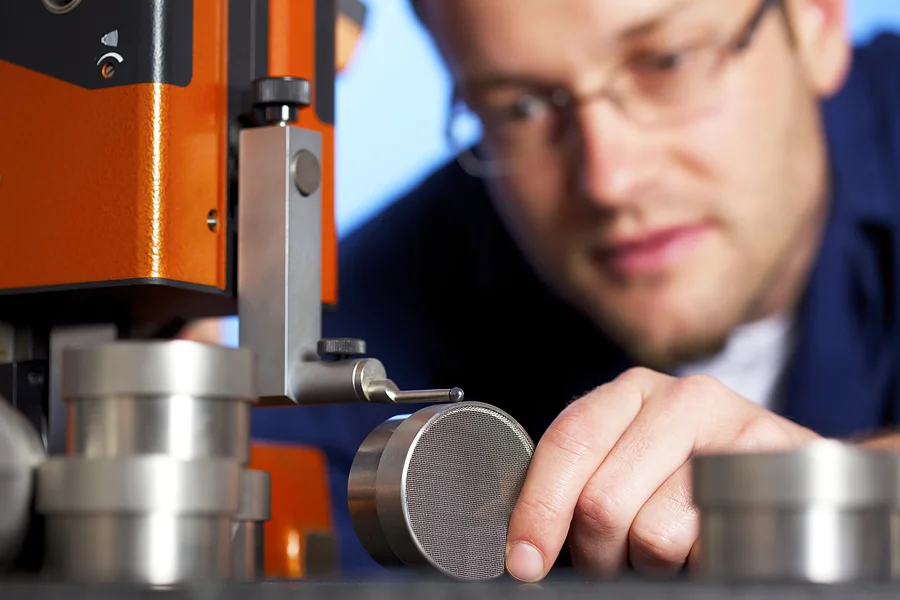

High quality data

Now let’s discuss what high-quality data means. In doing so, we must open Lean Six Sigma’s equivalent of Pandora’s Box, Measurement Systems Analysis (MSA). Without a doubt, this tool is perhaps the most misunderstood and underused in the whole toolkit. Yet, it is among the top tools we ought to use. This discrepancy between the necessity to use and actual use is a problem. MSA protects us from collecting poor-quality data that can be misleading.

MSA is an important technique. It statistically explains the amount of error in our data values which is caused by the act of collecting it. Obtaining a measurement value is far more complex than many people realize.

The measured value we record is derived from the interaction between the thing being measured, the measuring device, any people involved, the method they follow, the environment, and any digital systems in use.

In Lean Six Sigma training we teach MSA as a statistical tool. For me, it is also a principle.

For every bit of data, have we:

- Assessed the collection process for how it can go wrong?

- Performed the technical MSA (Gage R&R or Attribute R&R) assessment?

- Acted on the results?

The digitization of data only removes us further from the actual collection process, making it unseen and unknown. Data is served to us on screen, and automatically we trust it is good. Unfortunately, all data is collected from somewhere using a process.

How bad can measurement error be? Every single company I’ve worked in has had measurement systems errors. It is unpredictable in the level of goodness or badness. People who measure things all day long can be unaware that what they measure and report is poor quality. It’s not their fault, as typically, it’s always been done this way. Measurement error blights startups, SMEs, FTSE companies, and even multinationals. No one is safe.

Even data collected by calibrated and digital devices can go wrong. In a well-known UK steel plant, we saw a change in the temperature value on a key process metric. A team was set up, and investigations were undertaken. No root cause could be found. A team member met the maintenance lead of the temperature probe being used. The device had recently returned from off-site calibration. They asked to see it in action and went lineside. Immediately, the maintenance lead said, ‘Oh’. Post maintenance, the device had been re-installed in a slot 1m away from the intended position. The interaction of the device and the environment caused the change.

Across the globe, senior business leaders are blissfully unaware that their decisions are based on poor-quality data that masks the truth. Decisions are made, action is taken, and money is spent. Results do not change.

If you take one thing away from this guide, let it be this. When you measure a process, please perform MSA on the process data before you sample it. Let’s at least ensure that your projects are based on sound decisions.

4. Collection of qualitative data related to the project

Many projects need data on defects. It is a staple data collection item to help improve quality via subsequent root cause analysis. Collecting defect data can need significant time as, typically, and thankfully, defects tend to be on the rarer side.

If no historic data is available, then we’ll have to collect defect data over several months to build a representative picture.

Ensuring high-quality defect data is important. Where we use people, or even machines/AI to capture and classify defects, it is worth evaluating the measurement system using Attribute R&R.

Other qualitative data includes grouping, or classifying, variables. These can be organizational – teams, functions, departments, sites, countries, and regions. They can be equipment-related – line 1, line 2, etc. Any form of grouping variable can be collected here. The key is to ensure it is collected alongside your other data.

5. Collection of Supporting data related to the project

Other data we often include in projects is supporting data that frame the process in the business context. Typically, this is data like FTEs, overtime, input material costs, and productivity. Like any other data, the source quality should be checked out.

Anything, where time data is manually recorded or derived from manual activities (like clocking in and out), should be understood from an error perspective. It’s a fascinating world to assess, as people can devise multiple ways to record times. Rounding is the largest source of error with time data. Oddly, it’s rarely rounded down when it comes to payment!

Manual Data Collection

It is common that we collect data manually for a sample. If we ask others to do this, it’s good practice to test the data collection method upfront and for everyone to practice it where possible.

Where a collection method exists, and the MSA is sound, you should follow that method. Rather than make up your new method, if the MSA results are bad, fix the issues the MSA highlights.

Whenever data is manually collected for our project, we should check the first few data points. Talk to those collecting it. Ask questions on how it is working. Evaluate, and if it isn’t right, stop and fix the issues.

There is nothing worse than having to redo data collection because of an embedded error.

What Data Should We Collect?

There is an aspect of this that is purely project related but interestingly, there are common metrics that you always seek to collect based on the type of problem you are working on. The most common are summarised in this table.

Common Metrics By Improvement Activity Type

DateTime stamp

Grouping variables

DateTime stamp

Grouping variables

DateTime stamp

Grouping variables

Measure Summary

The aim of collecting data is to enable us to understand how the current state operates today. We do this so we can:

- Identify improvements via the Analysis phase.

- Compare against the to-be performance such that change, and benefits can be determined.

To enable these aspects to happen, we follow these three themes through the Measure phase:

- Only collect data for what you need.

- Always assess the data with MSA principles and, where necessary, techniques, before you collect it.

- Check and validate the initial data that you receive back.

And that moves us neatly into Analyse.

Analyse – Fact Over Fiction

If Measure is the most confusing phase, Analyse is the most eye-opening. Unfortunately, it is also where most mistakes occur.

The purpose of Analysis is to generate actionable insights from our data collected in Measure.

In this phase, we are bringing together multiple perspectives on the process so that we can progress into improving the process based on fact.

This aspect of factual progression is what differentiates running DMAIC projects from everything else. The analysis phase brings the rigour to our change process. Without it, we remain firmly in the realm of gut-feelings, experience, and say-so.

Just What is Analysis?

Many people view analysis as tools, a view which often stems from the focus in their training. It isn’t. Any tool is a means to an end, and that end is the obtaining of an actionable insight. Great analysis is 60% about asking the right questions, 20% collating and structuring the right data the right way, 10% about performing the analysis, and 10% generating solid, insightful conclusions that lead to action, just as the process below describes.

Analysis is a transitionary phase. Define sets the basis of what to measure. Measure enables Analysis. Analysis enables us to take the right action in Improve. We are transitioning from our theories on this process through to action on this process.

Analysis doesn’t just mean hard core statistical data analysis. It encompasses process analysis, defects analysis, comparisons between groups, and indeed any other form of analysis you need.

As practitioners, we should be aware that the tools in DMAIC are not definitive. Lean Six Sigma could blend much better with other analytical areas. For example, in people centric changes, behavioural analysis might be welcome. In very data rich projects, the tools and structures of data and computer science would help immensely.

There is no limit to what we can analyse nor the way in which we conduct our analysis other than our imagination. Therefore, we should aim to perform the analysis we require to answer our project questions, rather than be constrained by the tools we know. If we lack the skills to do it, don’t let that stop us, let’s find someone who can.

Answering some questions requires you to do something different. Many times, I’ve found myself developing code to first manipulate complex data sets together, second to generate some custom algorithm, and third to chain together statistical analysis. You can’t do that process inside statistics software.

The amount and depth of analysis undertaken can vary tremendously from project to project. For example, in a streamlining type of project, you probably wouldn’t do a great deal of data analysis beyond a few histograms and evaluation of basic statistics of process parameters. In these projects, analysis is more process analysis. Analyse the process to find the wastes, identify the value, so that we can re-design it in Improve.

However, if we’re trying to unravel a complex process issue, we may be buried deep in the technical data side with control charts, hypothesis tests and regression.

Hence, the analysis we perform is dependent on the problem we are trying to solve. This can make it harder to see how to navigate Analyse, especially on the more data rich side since many tools are dependent on things like the underlying data type and distribution shape. We have to learn these steps which will help us avoid making mistakes.

If I’m going to analyse some data, I always examine the data type first. Knowing this guides me to use certain tools that work with that data type and excludes all those that don’t. Let’s say my data is continuous in nature. I’ll then look at a histogram of the variable(s) with a normality test. This enables me to determine if the data is normally distributed, or not, and again, pre-selects which tools and statistics I can use in the next part of the analysis. By knowing these filtering steps, I can quickly get to the tools I need to answer the questions I’ve asked.

As our experience level grows, our confidence in analysis does too. As we’ll see shortly, confidence when performing analysis is important.

Choosing the Right Tool

There are so many tools available to us in Analyse, it can be difficult to select the right ones for our projects. Whilst I talk about asking the right questions, there is some generic guidance I can give as to the tools you tend to fall back on for different problems and types of analysis. Some of those tools are data led, some are not. The sheer number of them and how they link together underpin the difficulty of selecting them. Commonly used tools are shown in the following table, but this is by no means complete!

Commonly Used Tools By Improvement Focus

Remember, this is not all the tools! It’s easy to see why people have difficulty. It’s not just new practitioners either. For example, experienced practitioners forget to test their data for normality and use means and standard deviations to incorrectly describe the process behaviour of a skewed distribution. At Black Belt level this is a very basic error, yet it happens far too frequently.

Why we Make Mistakes in Analysis and Why we Don’t Notice

We’ve already covered the obvious sources of mistakes by using the wrong tool or basing our analysis on poor quality data. There are two more reasons that we’ll investigate:

- The way we were trained, and

- Our use of statistical software

When training in the Analyse phase, there is so much analytical content to get through that the time spent on each tool becomes limited. This means the focus is naturally biased to demonstrating the tool – teaching us how to use it in the software and interpreting the results. Sure, there is always some focus on the conditions of when we use it, but this understanding is secondary to the tool and output.

Couple this with the number of tools and it is little wonder that people leave their course confused.

If you have progressed through further education, then you’ll understand when I say that the way we train the technical content across belt levels is like the progression from GCSE (Green Belt) to A Levels (Black Belt) to Degree (Master Black Belt).

As we progress through different belt levels, additional knowledge, skill, and application is added for the same technique. We may not be aware of this situation since we tend to accept our training as ‘complete’. This can leave us exposed to making mistakes as our knowledge and skills are, as yet, incomplete. Whilst this situation can happen at any point when running a DMAIC project, it happens with more consequence in Analyse due to the associated decision-making aspects.

If you want to understand this deeper, feel free to check out this article – Understanding the limitations of your lean six sigma training.

And, for an example on how to resolve this issue, check out our article on Regression – A New Way to Teach and Learn.

Who Performs the Analysis?

Anything technical/statistical is usually down to us unless we’ve got lucky, and a team member can undertake some.

Process analysis should be led by us but it’s not necessarily up to us to do all the work. It’s OK to ask someone to complete activities like a cycle time analysis if we help them understand how to do it and keep an eye on the content.

Where we can, taking a little time to show and coach people new skills is beneficial, and during a project is often a good place.

In some projects where there is a large technical/statistical analysis that will support the process analysis, I’ll undertake that technical work ahead of the workshop and bring it to it. That way, I can manage the time and focus on the process analysis better, which is much more team orientated.

When to Stop, When to Loop Back

Paralysis by analysis. People love that phrase. For some, it gets pulled out at the mere sight of a standard deviation. We should ignore it but recognise that it can be a real problem in data rich projects.

Knowing when to stop an analysis is a crucial part of this phase. There are no hard and fast rules, other than to assess if we have generated enough insight to be able to move on and improve the process. Let’s look at our options:

- Yes, we have enough insight: Move on.

- Maybe: Ask if we can move on, or can we move on and plug the gap in parallel, or do we need to stop?

- No: Then we probably need to stop and get more data as it’s likely we’ve collected the wrong, or incomplete, data.

Never be tempted to keep analysing for ever smaller insights. At some point, every project will have reached a moment where enough insight has been generated even if it is incomplete. Remember that the aim of any DMAIC activity is to deliver an improved process and realise a benefit. You can’t get to that point if you remain resolutely analysing.

Communicating Analysis

Analysis is a technical subject area. It is packed full of terminology that your average worker will not, nor wish to, understand. It is our responsibility to ensure that what is communicated is written in understandable language for our audience.

If you present statistical charts or tables, call out the points of interest and annotate them. I highly recommend you do not let your readers draw their own conclusions. You’ll end up with different conclusions and arguments about who is right.

Analyse Summary

Analyse allows us to identify the factual evidence that underpins our current process performance and understanding of the problem.

The range and technicality of some of the techniques and tools requires us to validate our use and demonstrate (to ourselves) that the tool is the right one.

Interpretation of results can also lead to error. We need to be confident that our interpretations are correct and unbiased.

Finally, remember that analysis is a means to an end and it’s the end that really counts. We want to make factual choices about what and how to improve, but we must also balance this against the needs of customers, the business, and our stakeholders.

Improve – Creating The Future

The improve phase is a game of two halves.

Our focus in the first half will be on designing the solution and getting sign off.

In the second half, we create the solution and deploy.

Come full time, our lovely solution will be live, and we can move into Control.

Let’s look at how we set up for the first half.

Improve Part I – Ready to Deploy

1. Let Our Creativity Flow

Every DMAIC project has to transition from the wealth of insight it now possesses to a set of solutions. Solution development is a creative process and that means it involves the project team. Sometimes we find we need to add new people to the project team or change team members for this stage. That’s OK, just be clear why this is happening.

So, how do we transition from analysis to solution?

Some things are fairly obvious, like the wastes we identified, we can just strip that out of the process and start to build a solution (see 2. Design Solutions For The Process). Even in this, where the waste elimination forms the core of the solution, there is always plenty to discuss and get creative about.

Other aspects may still be unclear. Such as, we’ve found the root cause of a problem in Analyse, but the solution is not clear. In these situations, we need to use techniques like brainstorming to help us generate possible solutions and then, perhaps, some solution selection technique.

The solutions we develop are typically organised around process, equipment, facilities, systems, or people. We won’t really know which of these apply to us until we reach this stage in our project.

2. Design Solutions For The Process

Most projects will create a process solution. This is where we will plan to alter any aspect of the current process. Process solutions are focussed on the creation of the new process, called the ‘to-be’ design.

When looking at the activities and decisions that make up the process, there is a simple way to do this and a slower, more difficult way. Simple it is.

Start With The Best Option

If we think about it, the very best process will only have value adding activity in it and no handoffs. All pure wastes will be gone, and all business value-add will be tested for elimination. This gives rise to the simplest and fastest possible process where all activities are conducted by one, yet to be defined, team or set of equipment.

To create a to-be process, I take the value-adding and business value-adding elements of work from our process map and place them on a new map. Remember, we would have removed the wastes from within an activity, so these are the pieces of work that remain. I always place this new map on a different wall to the current state, preferably the wall opposite. It’s a psychological thing, we are physically and metaphorically, turning our back on the old way and getting focused on the new.

Permission To Change

Now, what’s on the wall in front of us, is most definitely a theoretical process. We must now attempt to fit that into our business. This is where it starts to get tricky, as how far we go depends on our remit from our sponsor, and that depends on our level of permission.

I find asking for these permissions in my initial sponsor discussion way back in Define is the best time to ask. It gives my sponsor time to reflect if they can’t provide an instantaneous ‘yes’.

Do we have permission to do these things or not?

- Shake up teams or departments?

- No? Put the activities back in their original swimlanes.

- Yes? Decide within the project team if any existing team is best suited to that task or if a new function is required. It’s quite common that no agreement can be reached due to personal attachment to functions. Be prepared to take this back to our senior stakeholders. Engage with HR in the design of changes to explore employment consequences.

- Move work from one team to another?

- No? Leave the activities in their original swimlanes.

- Yes? Examine workload balancing within and across tasks and select the best way to level the workload to improve flow. Move the work on the map. Engage with HR in the design of changes to explore employment consequences.

- Make system changes, like IT changes?

- No? Think how the new process can work within the constraints of the existing IT systems.

- Yes? What would ideal look like? Recognise that by making these changes we will be pushing out timeframes, potentially considerably, and introducing spend. Get IT involved as they are likely to be far better at designing systems changes than us.

- Spend?

- No? Live with it. What can we achieve at no cost or next to no cost? It’s usually far more than you may believe.

- Yes? What can we achieve at no cost or next to no cost? If we achieve this first, is the extra spend on further solution elements, or a different solution worth it?

A couple of notes on permission to spend.

First, it’s rare that I ask for a budget at the start of the project unless I think that getting to the solution design will incur expenses or there will be a cost for a few activities, like MSA and calibration, or data collection. Most projects just use people’s time when completing D-M-A-i.

Second, I always have this conversation on solution spend with my sponsor up front in Define. It goes something like this, “We’ll do our best to find solutions that are no, or limited cost but we won’t know until later in the project if we do need to spend on a solution. If we do, what would be the mechanisms for agreeing and arranging that?” With this statement, I’m trying to take the yes/no choice out of the response and force the sponsor to consider the possibility of spending. Often, I get a response along the lines of ‘it will need a business case I can take to the Exec/Board/Leadership Team’. Leaders aren’t stupid. If there is a genuine cost-effective benefit to be obtained and the project is linked to a strategic goal, they will look at ways to find the money.

Refine To Final Design

OK, let’s get back to designing our process solution. Our aim is to slowly loosen off from the theoretical best process back to one that is deliverable within the constraints we are faced with. In essence, we are introducing waste back into the process! It is the antithesis of what we have been trained to do. However, the reality is that in many businesses it is necessary for the project to complete. Do not hold out for the theoretical best process if there is absolutely no way the culture or leadership of the business will allow it.

We are far better off obtaining 80% of the theoretical benefits than none. This is a just live with it, pragmatic approach.

It doesn’t take too long to create this slightly-less-efficient process design. What needs to be added back in is fairly obvious. However, this is not the final process.

Our next step is to now refine it. Refining it includes exploring many aspects. The top ones are:

- Redesigning flow and layout. This might lead to production workstations being moved, or co-locating teams, or moving shared printers.

- Balance workloads. This is the splitting of activity across roles such that the process is balanced better to meeting demand. Takt time is very helpful here.

- Error proof the design. We use FMEA and Mistake Proofing to make our designs robust to the failures and issues we faced in the original process.

At the end of this work, we’ll have a process design that flows well, is balanced and is robust to failure. Who doesn’t like the sound of that?

3. Design Solutions For Equipment & Technology

During the creation of the process design you may have identified a need for new or amended equipment, or technology changes such that the new process will work.

The process is different as these items will need to be designed, procured, tested, and built. They usually require support from outside the project team and the business.

There may be internal processes that you will need to follow. Procurement, finance, engineering, IT are the usual suspects to engage with.

If we do go down this route, we should think hard about the project management that is needed.

Many times, I’ve brought in a project manager to oversee the process of design-procure-test-build-install as they are better qualified than I to lead this. I retain oversight since it’s my responsibility to ensure the solution is as intended. I also have input, usually to confirm the understanding of the design with vendors, ensure completeness of test plans, and align change management through the installation.

From the perspective of our project, we will need to understand timelines and implementation aspects so we can advise stakeholders and the functions receiving the change. We also need to align our thinking on change management as well so that we are prepared for implementation.

4. Use The Power of HR

If we plan to make any changes to people’s roles, we must engage with HR. With HR being a much more integral part of business than ever before they are in position to veto or seek to amend people related changes.

From a people care perspective this is a good thing as it adds a layer of protection. HR also provide us with the checks and balances in what has become a legal minefield.

However, involving HR can often slow a project down due to these complexities.

Getting HR time on a project can be difficult, so it is best to have an HR contact as a stakeholder. I’ll talk to them upfront in Define and have them on standby to join us during the solution design. Choose someone who can provide advice about the roles that will potentially be impacted and can make decisions on role movements. Sometimes, that’s two people. I do this for every project that has a process element to it that involves people, i.e., pretty much every project.

In this context, the HR role is not to prevent change happening. Rather, it is to help with the following that may apply to our project:

- To ensure that what we propose to do is legally possible without recourse, or to help us understand and overcome any potential recourse.

- Examine employment contracts for impacts based on our proposed changes and advise.

- Assess salary impacts if roles are taking on additional responsibilities.

- Open and manage/support dialogue and process around role changes, movements to a new team, redundancy (the latter to be avoided as far as possible!)

I cannot stress how important it is to work with HR in today’s environment. Please, do not assume ‘it will all be OK’ without their input.

5. Design Sign-Off

As we progress through the design of the various elements of our solution, we need to have one eye looking ahead to schedule in its sign off.

The formality of this event depends mostly on the cost and impact of the solution.

With small, localised process changes we can run an open-door session with the key stakeholders, describe the new process and changes, and obtain sign-off within the workshop itself. We must ensure our stakeholders are given enough notice to free diaries.

Progress through to large cost, high impact, multi-geographic changes, and we find ourselves moving to more formal meetings, briefings and decision making. The scheduling of this is often more complex so the earlier we can put this in diaries the better. Use that fixed date to drive the team to complete.

6. Create The Solution

Aspects of our design may require physically building or making elements, like new or changed equipment. Completing as much of this activity ahead of implementation will make implementation faster and more robust (see piloting).

What else should we do ahead of implementation?

- Update our process documentation. This includes new process maps, SOPs/work instructions, role descriptions, layout diagrams and so on. Create it, and get it peer reviewed and signed off.

- Update our data collection plan fo cover:

- Process metrics to confirm performance of the new process is where it should be.

- The collection of data necessary to confirm benefits.

- Create, peer review and sign off all our training components.

- And all being well, we would have started change management assessments of our changes that we identified during the creation and sign-off of our designs. If this is not underway yet, start now!

7. Plan for Implementation

Every implementation should have a plan. It might just be a few lines long at times but a plan it is.

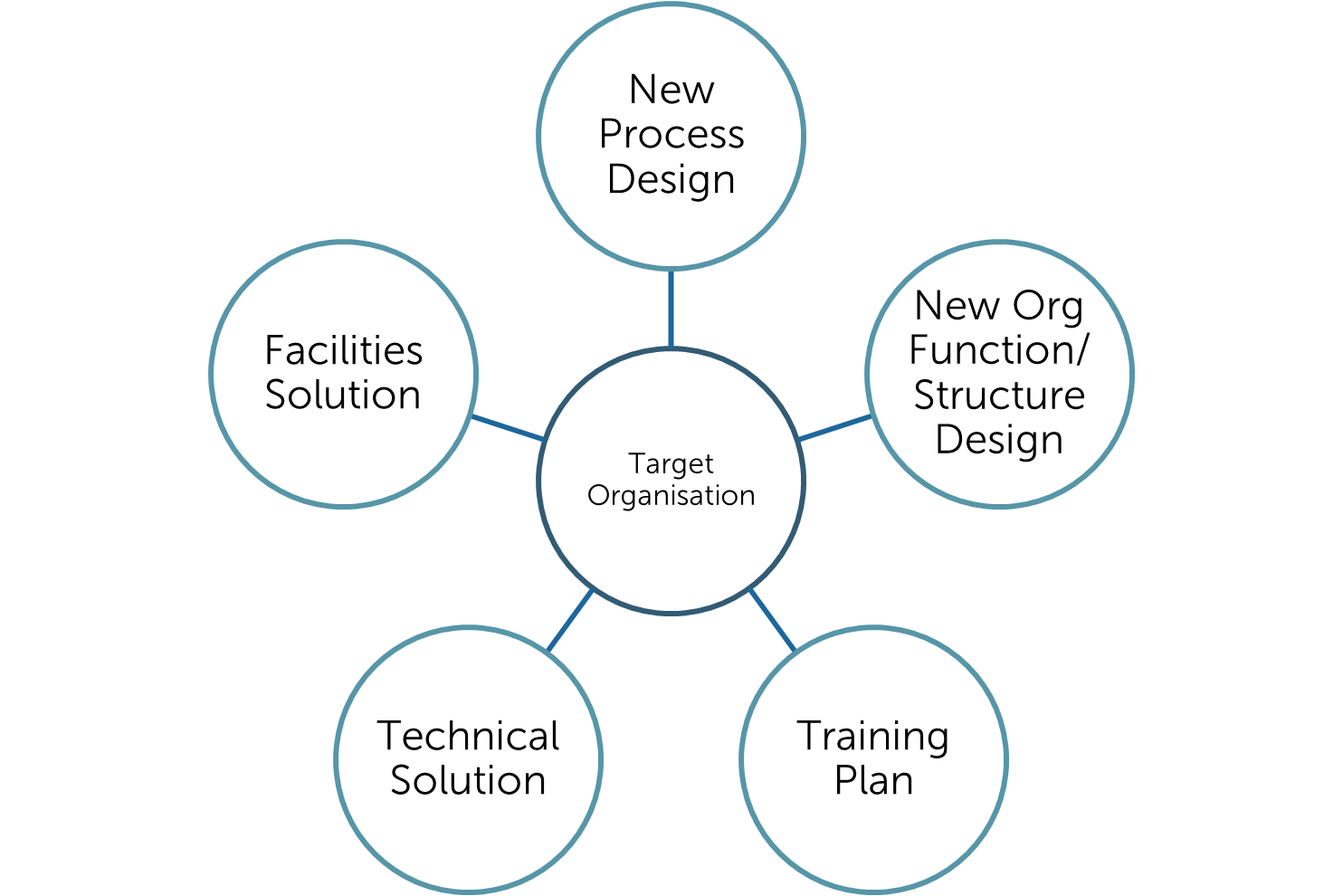

To create this plan, we integrate the multiple elements that we’ve been working on to our target organisation. This includes: our new process design, any technical solution designs, facility designs, changes to functional or organisational structure and our training plan.

Our integrated plan outlines:

- what is changing,

- how we will perform these changes,

- the deployment sequence,

- dependencies within those changes, and

- who is impacted.

Wrapped into this planning will also be any actions from our change management assessment.

The project team can’t create this plan alone. Often, we’ll need input from stakeholders so that we can finalise dates and dependencies. Never assume we can access a production line, or a team without consulting first!

We should also understand the environment we are deploying into from a sponsors perspective. Companies are not the same and their appetite for realising change differs tremendously.

I’ve worked with many companies across multiple sectors. When it comes to implementation, every company has a different view. A bank I worked in said, ‘take your time, we want no risk’. An IT Service company said, ‘we want it now, manage the risk.’ This difference in approach dictates how much robustness you need in your solution planning.

Generally, we can think of our deployment approach in two seperate dimensions: the speed at which our organisation is asking us to achieve our project (slow, medium, fast) and the risk to the business of the change (low, medium, high). Based on our assessment of these two dimensions, we can use slightly different approaches to ensuring our plans are robust and ready for deployment.

Assess Project Speed

Obviously, faster projects mean less time. We’ll have less time for testing or piloting, so we’ll need to focus that on critical areas of the solution. In cross functional projects, we’ll have to deploy to more teams at the same time, so either a ‘big bang’ or overlapping rollout approach. The level of presence of the project team can differ too, with faster activity requiring more team members to be on-site to support.

Assess Deployment Risk

The second dimension is the risk the change may cause to business operations. Again, the higher the risk, the more work we should do up front. High risk changes, like significant changes to a core business system or production facility, can result in significant business loss. In these situations we should ensure that our process and technical designs undergo FMEA and error proofing. That we have back out plans and disaster recovery in place.

I spent a long-time leading improvement in an IT service provider. Every project that changed an IT system had a back out plan. It was the same in banking. The more risk the change can cause, either to internal ability to deliver or direct to customers, the stronger the backout plan needs to be.

Training must be thorough and supported by on-site project team members.

Sometimes these two dimensions can be in conflict. If our sponsor wants a fast deployment but no risk, we’ll need a discussion on the preference. Explain what we need to do in each scenario and reach an agreement on how to resolve this conflict.

Share The Plan

It’s easy to think that the output is an implementation plan the size of a best-selling novel. In reality, use the above sections as a guide and be pragmatic. The only relevant question is ‘Does our integrated implementation plan cover everything we need?’

One of my very first projects took six months to complete. It was technically complex to solve, requiring me to develop a production line computer simulation from scratch. Many people were involved in getting the correct inputs for the simulation. There were many iterations of development as I refined the algorithms. Eventually, the sim gave me a solution. No people were impacted, only software needed modifying, and no training was required. The implementation plan was two tasks: ‘change code’ and ‘test’. The backout plan was one line: ‘revert to previous code’. Implementation took 20 minutes for an engineer to update the process logic controller (PLC) whilst I and a few bosses stood lineside. The line restarted and the solution worked. We watched a few cycles to confirm it worked. It did, perfectly. Everyone walked away happy having secured a minimum of £2m a year of benefit. Integrated implementation plan pack size – one side of A4.

When we have created our integrated plan we share it with our stakeholders and confirm.

Finally, we use all our content to develop brilliantly informative and engaging implementation communications and start the process of communicating ahead of go-live.

8. Run a Pilot

Piloting is an optional step as it is very much dependent on our solution. We can run many different types of pilot, but the one we tend to use the most is partial piloting.

Partial piloting is, as its name suggests, testing part of the solution. This could be testing on one member of a team rather than the whole, the part of the solution we deem most risky, one production line rather than all, or one site rather than all.

We get to choose. The aim is to try and find out how performance is related to our expectations and to test any areas we might lack confidence in.

Depending on the results we would either proceed or adjust that element ahead of implementation. Don’t rule out running the pilot again if things were a long way from expected.

Improve Part I Summary

Is it worth it the effort of planning implementation? I promise this, there is nothing more stressful than the combination of a disastrously chaotic implementation coupled with high leadership expectations. Yes, it is worth it.

Improve Part II Implement The Solution

If the aim of Part I in Improve is to enable our implementation activity to run as smoothly as possible, then Part II aims to ensure that it is achieved. Whenever we run a DMAIC project this is the part of the method we should always have as a primary focus. When we reach this stage, we are an implementation away from success.

Let’s find out what we need to work through.

1. Execute The Plan

Now we can turn to implementation which is a case of executing our signed-off plan. Step by step. Manage it, lead it with style, communicate, and adjust as necessary.

Advice for this stage? Get involved. This is not a delegable activity. Be there at the pointy end and see the solution implemented. Whether that’s a physical solution or a people solution, be there. It will enable you to observe how the solution is working. To see if those training materials work in practice. Understand how are people reacting to it.

Involve the project team as well. Get them to take some ownership of being on point during deployment. It’s a tremendous personal development for them as well as taking some of our load away.

Don’t be afraid to make changes either, or to put aspects briefly on hold to clarify. It is the outcome we are working towards. Plans and designs are great, but the reality of live running counts for more.

Communicate and engage. The change management aspect is very important here. Helping people start their individual journey of transitioning to the new process is essential. The more we, as a project team, support that during deployment, the better the outcome will be.

2. Measure New Performance

If we’ve planned well, data will be coming in from the very start of new operations. Collate it, chart it, assess it but don’t react. Very often new processes take a little time to bed in as people come to terms with it.

Rarely will I adjust anything until the process has cycled enough times to give me evidence that suggests we are not on track or won’t get there with time. I keep Deming’s thoughts on Process Tampering front and centre in this time. It helps me guide others not to panic and overreact.

If we have set goals for the project, it is here where we will resample the process in the same way as we did in Measure. This data may take some time to collect if the process cycles infrequently, in which case, we will allow this activity to roll into Control.

When we have a new sample, and if necessary (big differences don’t need testing), we can then perform hypothesis tests to statistically prove a change has been made. From this we can make a practical determination on the magnitude of that change.

It is always possible, albeit rare, that we would conclude there has been no difference made by our changes. This tends to happen when projects are very focussed on say, a single characteristic of a process. In such cases, if the process performance is not worse, the new design can be left in place assuming that no downstream consequences arise. If there are consequences, back it out.

3. Observe, Listen and Learn

Also understand that every deployment has an additional purpose. It is for us, as the project leader, to identify areas to improve the process next time.

What works, what doesn’t, and what could do with a tweak?

Being present during go-live is the fastest and best way to up our game in future deployments. Make notes and be sure to review them in Control.

Improve Summary

The Improve phase is entirely focused on reaching a deployed outcome. Typically, that is a new process design – either a full or partial process, along with any trimmings like equipment and system changes.

How long we take to complete Improve is entirely solution dependent. Part of the skill in running DMAIC projects is to be able to keep this phase to the minimum without compromising on solution quality.

Control – Assuring The Future

The control phase is concerned with the transfer of responsibility of the new process to the process owner and to ensure that performance gains we expected are achieved and held. We also confirm that benefits have been met. Lastly, we conduct a post-project review, share lessons learned and shut down the project.

We know we’re nearly done when the project team has let go of the new performing process, ticked off a few formalities, gone for a nice cup of tea, and the conversation has switched to the next project.

Handover

Control begins by handing over the new process in its entirety to the process owner.

In essence, this comprises passing over many of the outputs associated with the process designs and training materials. These outputs should be updated following implementation and placed in the appropriate place, like the Quality Management System (QMS). Who does this is a discussion between the project team and the process owner, but usually it’s the process owner.

Depending on the nature of the change and the process you may also need to inform your QA department so that internal auditors are aware of what has happened, and their audit schedule can be updated.

This will ensure that usable process content is placed under change control and undergoes an annual review.

Controlling Performance

The second aspect is one of ‘placing the process in a state of control’. This can mean different things for different projects, but the intent is the same. We are looking to ensure that our process performance is both stable and predictable, meets any customer expectations i.e., is capable, and runs in accordance with the expected designed performance.

Therefore, this aspect of control becomes about data and using that data to demonstrate the above.

There are two charts that help us greatly in this respect.

- The control chart (aka SPC or process behaviour) chart which demonstrates statistically if the process is meeting the design intent, and in addition, if the process is stable and predictable.

- The capability chart/analysis which demonstrates if the process performance is meeting customer expectations.

Taken together, this is all we generally need to show performance. Please, forget about tables of information, bar, and line charts, and just use these.

If performance isn’t being met, we have a couple of choices.

- Wait a while if the process is still bedding in AND we think it will reach performance. If so, it is OK to finalise handover and for one or two project team members to keep a watchful eye on performance. Or,

- Act, make some additional changes.

Confirm Benefits

The third aspect of control is to translate our new performance into benefits. These should map back to our goals and original benefit plans. Depending on the rigor in our company, we may need to get help from other teams, such as Finance, to validate hard, or tangible, benefits. This is important, especially if they will end up baked into the P&L or Balance Sheet. We can check with our Finance team how hard benefits can be realised.

Soft, or intangible, benefits should also be listed and evaluated. Sometimes these will outweigh the hard benefits so expressing these is also part of our benefit reporting.

Post Project Review

Now we can move onto the post project review. This doesn’t have to be a big formal exercise, but it is an opportunity for the project team and stakeholders to make comments on how the project was delivered. Look positively on this activity as it has the power to greatly enhance your knowledge and ability to deliver, as well as help the organisation make overall changes to project approaches.

It can take the form of a survey, which is useful if many members are off-site, or as one or more videoconferences.

If using videoconferences to capture project feedback, I suggest organising one call for senior stakeholders and leaders and another for staff. You’ll generate more feedback, both in quantity and in quality.

Project Shut Down

Finally, it is time to shut this project down and celebrate its success. There may be some formality to this regarding the project itself closing out project registers and cost codes etc.

Then, we – us as project leaders and the sponsor – thank people. In this order. Thank the impacted staff for their commitment to making this change a success. Then thank the project team personally as a group. A little thank you lunch with heartfelt speeches by you and by the sponsor goes a long way for buy in. Both groups can be thanked at the same time if logistics allow.

Finally, always personally thank the sponsor and process owner, and as minimum, email/group call other stakeholders to thank them for their support.

If a project team member or an individual impacted by the change has gone above and beyond, provide this feedback to their leader. They will appreciate us taking the time to do this come their annual appraisal.

No matter how the project has gone, say loudly and proudly how this project has ‘been a delight to work on’!

Control SUmmary

By the end of the Control phase the process should have been handed over with established working performance control measures that are prooving that performance is meeting goals or to an agreed level.

When these are in place and signed off by the Process Owner we can move on to formally shutting the project down.

This involves confirming benefits, conducting any post project reviews and formally closing the project.

Every project must close and say “goodbye” to the problem.

But be aware. Too many projects fail to close. A major cause of this arises during implementation where new problems are surfaced that were originally out of scope. Our sponsor or Process Owner asks us to keep working on them. Watch for this as these projects can quickly become jobs for life.

Unless the issue is of burning importance and related, if a senior stakeholder asks me this late in the project to bring something else in scope that isn’t trivial, I say “No. Let me close this project out and we can take a look at launching another for this.”

Stay focused on the end game. Close your projects. Keep the cadence and cycle of change going.

I hope you enjoyed this guide. If you would like to receive more content on performing business improvement and change, feel free to sign up to our email list.

Happy improving everyone – keep running those DMAIC projects with success!

0 Comments